Investors all around the world favor stocks in their home countries over foreign stocks relative to global market capitalization. This is known as home country bias.

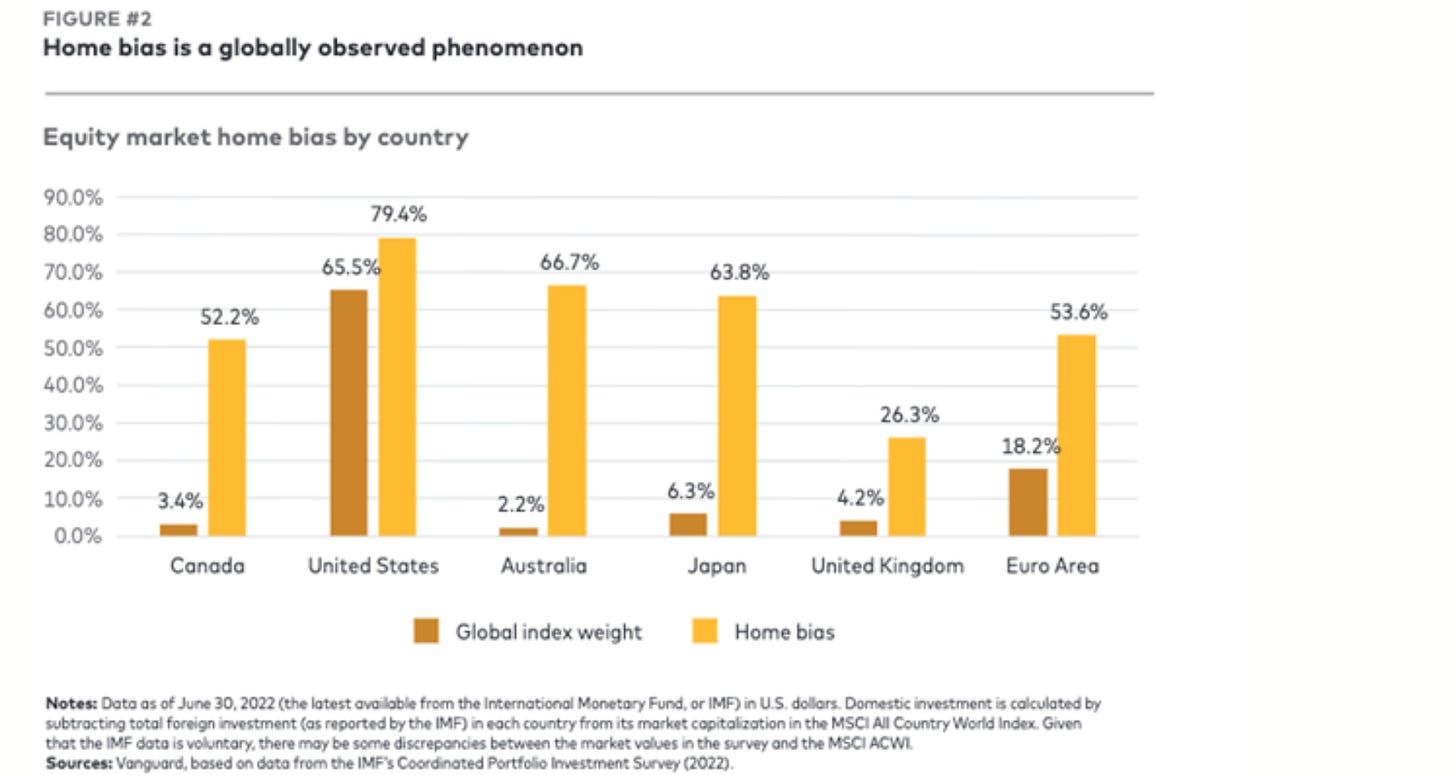

Take a look at this graph from a 2022 Vanguard Canada paper titled “Canadian Home Bias: A Case for Global Equity Diversification”. I can’t find a workable link to the paper but I do have this screenshot:

Investors in every market displayed here exhibit a strong home country bias. While Canada made up 3.4% of the global stock market, investors had 52.2% of their portfolios in Canadian stocks. That’s 15 times the market weight. UK equity investors overweighted their home country by 6 times, European investors by 3 times, Japanese investors by 10 times and Australian investors by a staggering 30 times. U.S. investors, notably, were only overweight by 1.2 times, perhaps owing to the already large share of U.S. stocks in the global market.

Investors display this bias anytime they own a larger proportion of their country’s stock relative to the global market cap weight of that country’s stock market. Home country bias is generally seen as a behavioral error. If you believe that markets are efficient, a market-cap-weighted portfolio is the optimal portfolio. Therefore, you should aim to not only own a market-cap-weighted index in your country but a market-cap-weighted index across the global equities market.

Any portfolio that focuses solely on one country or a handful of countries inherently seeks to pick winners and losers. This lack of diversification can be detrimental to your portfolio not only over the long term but also during shorter periods of severe underperformance for specific countries.

Among U.S. investors, it’s often taken for granted that international diversification isn’t necessary. You see this in common investing memes like “VTSAX and chill” which collapses long-term investing down to a single maxim: buy the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund and forget it. There are lots of issues with this that I covered last week. Certainly ignoring international stocks is a bad idea, but what about overweighting U.S. stocks if you’re a U.S. investor?

Likewise, if you’re Canadian, or British, or Australian or Japanese, is it wrong to overweight stocks in your country? While on paper doing so goes against common investing wisdom, the full picture is a bit more complicated.

The Cost of Home Country Bias

What is familiar to you isn’t necessarily what is best for your portfolio. Just as you shouldn’t “invest in what you know,” when it comes to specific companies or industries, you probably shouldn’t invest in countries that you know. You should aim to own a little bit of everything.

Home country bias suggests an overconfidence in one’s home market, and history shows that it can have disastrous effects. Take two of the most extreme examples. After the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917 and with the victory of communist forces in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, those respective stock markets were nationalized and investors experienced 100% losses on their investments.

Even developed markets aren’t spared from the risks of concentration. In 1989, Japan’s stock market made up 45% of the global market share compared to 29% for the U.S. After nearly a decade-long rally which saw a 450% return, the premier Japanese index, the Nikkei 225, suffered a massive bubble burst. As I wrote last year:

But the exuberance would soon end. In 1990, the index dropped 39% to 24,000 points, followed by a 4% drop in 1991 and another major drop of 26% in 1992 to 17,000 points, erasing the gains of the previous 8 years. The stock market continued falling throughout the 90s and early 2000s, losing about 80% of its value from the peak and falling to about 8,600 points in 2002. The index has slowly recovered since then to reach about 32,000 points today. For 30 years, the index has basically been flat.

Japanese investors who diversified internationally came out much better than those who were overweight Japanese equities.

Home country bias overexposes you to the risk of a single stock market. But we don’t need to look at catastrophic examples to see the value in diversifying internationally. Despite the well-documented outperformance of U.S. stocks since the global financial crisis, there have been times in living memory when international equities outperformed. From 1950 to 1989, U.S. stocks trailed international stocks by 2.65% in real terms. From 1968 to 1982, U.S. stocks returned -0.08 per year while international stocks returned 3.61%. And from 2000 to 2009, U.S. stocks returned -2.25% while international stocks returned 1.01%.

For U.S. investors, owning international stocks paid off during these periods. It would be short-sighted for investors today to dismiss international stocks when history shows that the U.S. doesn’t always outperform and that betting everything on one country can mean losing it all.

Is Home Country Bias Ever Justified?

Despite the clear risks of overweighting countries in your portfolio, there are some real benefits to home country bias. For one thing, domestic investors tend to receive preferential treatment to foreign investors, and when times get tough, countries will often throw foreign investors under the bus.

You see this when countries nationalize industries or impose capital controls, which has happened at various points throughout recent history. Foreign investors are exposed to higher risk than domestic investors.

Transaction costs associated with investing in foreign markets also tend to be higher than investing in domestic markets. For example, VTI, which tracks the total U.S. market, charges 0.03% in fees while VXUS, which tracks the international stock market, charges 0.08%. This is a minor difference for U.S. investors, but in many countries the difference is much greater. Foreign investors also pay more in taxes while often getting tax breaks for investing in their home countries. And sometimes home country bias is unavoidable if you live in a country with limited access to foreign markets.

So people who overweight their home countries may actually be making a rational choice, although none of this justifies the extent of the home country biases we see. Taking a modest approach may come with some benefits, but significantly overweighting your country is quite risky.

Now what about U.S. investors? How should they think about their own home country bias? I came to a realization while researching for this piece that U.S. home country bias is not nearly as extreme as it is for other countries.

Let’s go back to the bar graph from the beginning. U.S. investors overweight their home country by 1.2 times compared to 15 times for Canadian investors and 30 times for Australian investors. But unlike these other markets, the U.S. does make up a significant portion of the global stock market, about 60%. So even if you are invested in a strictly market-cap-weighted portfolio, the majority of your portfolio is already in U.S. stocks. If as a U.S. investor you allocate 75% of your portfolio to U.S. stocks, you actually have a lower relative bias toward your home country compared to a Canadian who allocates 50% of their portfolio to Canadian stocks, for the simple reason that the U.S. is naturally a massive portion of the global stock market.

That can change, of course. It might make sense to own 75% U.S. stocks when the U.S. is 60% of global markets, but what if we return to a situation like 1989 where another country has a decently larger share than the U.S.? Then it might be time to take a closer look at such a large home country bias.

Fixing Your Home Country Bias

While there are some rational reasons for home country bias, there are also plenty of irrational reasons, like patriotism or overconfidence in your own country’s future economic success. And even if your country’s GDP grows, that doesn’t mean its stock market isn’t wildly overvalued. Valuations have a huge impact on future stock returns.

Just as no one can know ahead of time which stocks will outperform the market, no one can know ahead of time which countries will outperform the global market. It’s certainly possible that the U.S. is truly unique and will continue to beat other markets over the long term. It’s also possible that bad policies or wars can cripple the U.S. economy and leave it behind the global market. The future is unknown. And for that reason, it’s probably wise for U.S. investors to not overweight U.S. stocks too much.

Naturally, the bigger your country’s share of the global stock market, the less home country bias hurts you. This is why U.S. investors can probably get away with this bias compared to countries with much smaller stock markets. But you still need to take some basic steps to diversify your portfolio and ensure that you adjust according to market cap weightings.